Years ago, if you had opened the door to the hostel room of Venkat Rangan, you would have been greeted by music. One could say tinkering was something he always latched on to, because the door’s latch triggered the music from a system he built himself. "He's always been a tinkerer," recalled Vishal Srivastava, who studied alongside Venkat and now leads Marketing and Business Development at the company. "We also built speakers and all that stuff together." In this feature, Vishal chats with CircuitDigest about how tinyVision started and what drives the thinking behind its operations.

Table of Contents

Edge Computing by Day, Education by Night

In 2018, Venkat founded tinyVision to leverage the need for smarter embedded devices, helping clients take their ideas from concept all the way through to execution. This includes hardware design, firmware development, component sourcing, and even manufacturing support at their San Diego facility. The company’s offerings can be broadly classified into two segments.

Engineering Solutions

The larger area of tinyVision’s expertise is in helping companies develop edge vision devices across sectors like medical imaging, robotics, and drones. Most of their tech centers on FPGA-based solutions that enable high-resolution, high-fidelity camera inputs with a focus on minimal latency and power consumption. This is something that differentiates them from the rest of the market, as FPGAs excel at accepting multiple input streams at once. Vishal explained, “Most of the solutions on the market are one-to-one; we have one sensor connecting to a microcontroller board that feeds it to the host computer. Ours is an FPGA-based solution, and ours is the only solution that can take in multiple feeds, and then either stack them, or we can stitch it whatever way you want, either as individual streams or a single stream, and give it to the host computer; very low latency, very low power requirement: 180 milliwatts is what the thing will consume.”

Educational Hardware Platforms

On the educational side of things, they make boards that let students and hobbyists learn HDL programming without breaking the bank. These boards help numerous universities and colleges in teaching digital circuit design. The scope of learning extends from logic gates to edge AI owing to its computational power. While the boards might not be hyper-capable, they can handle basic stuff like recognizing broader categorizations such as people, cars, etc. Vishal even shared how the boards have found their way into a surprising project. A company used these boards to build a controller for an automated pizza oven. The reason was its simple, open-source FPGA-based nature and toolkit, which together provide a great deal of design freedom.

How Much?

One major problem with FPGA programming has been accessibility. Universities might have expensive AMD boards in labs, but these are platforms that cost hundreds of dollars, usually $300 to $400. UPduino entirely flipped that equation, costing roughly one-sixth the price of a traditional FPGA learning platform. “Sure, it doesn't come with all the peripherals that you want,” acknowledged Vishal. “Our idea is that you can pick and choose the peripherals you want. If you want to build a display driver, you can buy a, you know, a segment display or an LCD display and hook it up. If you want to build a camera thing, you can buy a Raspberry Pi cheap camera for maybe 10 or 15 dollars and connect it.” He further emphasized how its inexpensiveness meant that students can have their own boards to tinker with as opposed to sharing equipment in a lab where they spend as little as 8 to 10 hours per semester. The opportunity to invest 30 to 40 hours in a project allows students to take on more demanding and focus-intensive work.

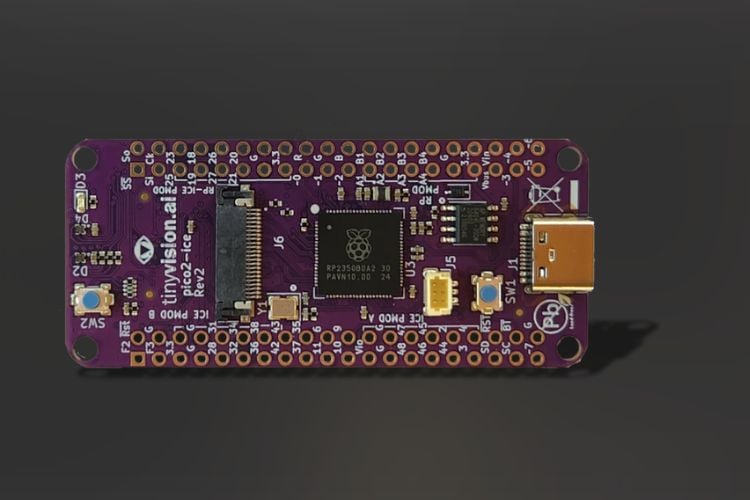

pico2-ice: The Community’s Ask

Building on community feedback, tinyVision developed the pico2-ice, which combines a Lattice FPGA(iCE40UP5K) with a Raspberry Pi Pico microcontroller (RP2350). Vishal described this as the approach the company took towards building anything. They went to their community proposing a processor add-on and were met with a lot of enthusiasm, and so it happened. The company plans on sticking to this route moving forward as well, and this is exemplified by the tentative name of their next board, “Pico Next”. When asked about what they have planned for the board, he answered, “We haven't decided. We just decided, okay, let's build the next one. So, we have asked our community about what they would like to see.” While the pico2-ice might not be revolutionary, it’s thoughtfully designed for a purpose. It essentially gives learners a way to learn incrementally. Someone can choose to start building right away, treating it as a plain Pico board and programming it in C or Python. After settling in, the learner has room to grow to the FPGA level, programming in Verilog or VHDL. The integration helps solve project complexity as well. In bare FPGAs, designing user interfaces and configurations at low-level is logically a nightmare, literally. The simplification of work extends to USB implementation as well, and another huge benefit is the reduction of resource cost.

Open by Design

You won’t run into proprietary roadblocks when designing with either UPduino or pico2-ice, as the entire toolchain is open source. The company also has an engaged Discord community of thousands where builders share and discuss their projects. This way you can run into a solution for a problem of yours or solve a problem a contemporary has. The company also has something in the works to develop structured educational material and sample project documentation so that if someone decides to start building something, they’re not left in the dark. Zephyr was a notable mention from the interview. “Zephyr is probably the most popular open source thing happening right now. And so, everyone is building those libraries on top of that. The one limitation is that, you know, anything you do in software is slightly slower than what you can do in hardware. If you implement the same thing in hardware, it's much faster, but then it's also more expensive to design and build,“ explained Vishal. “We'll continue to push very hard on the Zephyr open source stuff, whether it is for a client or we just build it ourselves for our product, and we push it upstream wherever we can. Sometimes you can't, because it uses vendor or OEM stuff, so you can't push it. “ He even shared how a good portion of the chip vendors he interacted with at electronica India 2025 are adapting to support Zephyr due to customer demand.

The Tinkering DNA Continues

After years in the corporate grind, Venkat found his way back to what he enjoyed doing, following his tenure at Qualcomm. This is when UPduino came into existence, and it arrived even before tinyVision did, as Venkat originally built it for himself. “Once he built it, he showed it to some people, and they liked it,” Vishal recalled. “And then one of his friends was a professor. He wanted to use it, so he said, 'OK, this seems like people can use it.’” It went from a tiny wish in Venkat's mind to tinyVision boards in the hands of students that combine open-source flexibility with FPGA and allow experimentation of everything from logic design to AI applications.

While it is true that tinkering is learning through patience and iterations, overly unfamiliar territories can dampen curiosity. With affordability and accessibility reasonably met, the obvious next step is guidance and reference material, which some might argue is the bigger elephant in the room for FPGA newcomers. With tinyVision eyeing this area as well, we are eager to see how it supports the transition of enthusiasts into the sink-or-swim world of FPGAs.