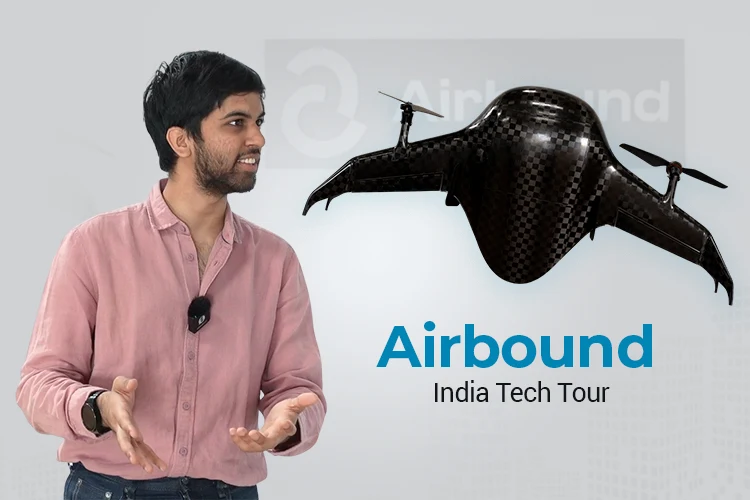

Airbound is a drone startup on a mission to make logistics virtually invisible. What the company imagines is an internet for postal codes instead of IP addresses. We explored their facility to understand what happens behind the scenes, and through this article, I'll try to piece together how they're engineering their way to that reality.

This feature is part of our India Tech Tour series, presented in collaboration with DigiKey, a leading global distributor of electronic components serving engineers and innovators across 180+ countries with a catalog of over 17 million products from 3,000+ suppliers.

To start with, the premise of drone deliveries at Rs 1 felt silly to me, not because I worked out the math, but intuitively. Thankfully, the company’s founder and CEO, Naman Pushp, worked out the math for us. Here’s how he presented it: Imagine a person on an electric scooter; the cost involved in moving a kilometer is roughly Rs 1.5 to Rs 2. This is what is spent to move 150 kg from one point to another. Whereas carrying a payload of 3 kg might require 5 kg in total, including the vehicle, which is down a factor of 30 from 150, and that should bring the cost down by a factor of 20, according to the company’s calculations. Moving less mass around should cost less, the argument goes, and that feels plausible even accounting for stuff like rolling resistance, aerodynamic drag, speed profile (stop-start vs steady), route grade, drivetrain and charging efficiency, fixed electrical and control losses, battery amortization, and maintenance overhead. Looks good on paper, right? Looks as good as paper, too... wait, what? I’m talking about the carbon fiber body of the aircraft. It was so light that it dropped like a sheet of paper catching air.

Anyway, let me not drop the details too soon. Let's disassemble this properly.

Table of Contents

Drone or Airplane?

Looking at Airbound’s TRT drone for the first time made me question my memory of what a drone looked like. It looked nothing like the familiar image of four blades propelling a small, buzzing machine. “They essentially look a lot more like miniature airplanes than your traditional drones, because that is absolutely what they are,” said Naman. “This is the same physics behind what makes a plane fly, and the difference between our aircraft and a plane is that we use what is called VTOL.”

The tail-sitter drone features a blended wing design with propellers sticking up from the top. It takes off like a cross between a rocket and a quadcopter and then tilts flat, giving it that airplane-like look. This VTOL (Vertical Take-Off and Landing) design is crucial for last-mile deliveries simply because residential buildings in the world we live in don’t usually come with landing strips. As Naman put it, these drones compare to quadcopters how bicycles compare to motorcycles: both are two-wheelers, but the capabilities are completely different. In summary, taking off like a helicopter and cruising like a plane lets the drone inherit the flexibility of one and the efficiency of the other.

One Kilo Payload, One-and-a-Half Aircraft

Spec sheets are usually boring, but this one isn’t. It’s counterintuitive and intriguing. When we asked for the numbers, Naman laid it out plainly: “Our drone carries one kilo of payload. The entire drone weight is about one and a half kilos,” he said. “If you just think about the frame, pretty much everything you see here visually, except for the motors and propellers, that weighs only about 350 grams, almost as much as my phone.” That’s three hundred and fifty grams of aircraft skeleton carrying a payload three times its own weight.

While the aircraft can fly about 37 kilometers in one go, the company is deliberately starting with shorter flights, likely because that means more operational data to refine things. Other specifications include a 1.4-meter wingspan and a lift-to-drag ratio of 12. It can cruise at 60 km/h, reach altitudes up to 40 feet, and operate quietly at 60 decibels.

The Fabric of Flight

Inside the Airbound facility, it didn’t feel like a drone factory…think Walter White running a covert lab out of a textile mill. Picture rolls of fabric, scissors, moulds, vacuum pumps, a refrigerator, ovens, and chemicals. Forgive the odd comparison, but there's a method to this madness. Airbound is less about trying to outsmart electronics and more about trying to outsmart air at the moment. Their drones are first and foremost a feat of aerodynamics and material engineering, with electronics playing a supporting role.

“A good way to think about this is looking at brushless DC motors, right? Brushless DC motors today are about 70-80% efficient. You can make your own; you can push towards like around 90-93% efficiency, but that's not a big difference. We know that with our own carbon fiber, with these other parts, we can get 10-20x better efficiency, but, you know, it's not physically possible to get beyond 100% efficiency with motors, for example, and so it's not worth pouring a lot of our own energy into them right now,” Naman made his point. “Over time, we do want to control every aspect of the supply chain, and we want everything to be how it ideally should be. But, of course, reality exists… some places you have to use off-the-shelf parts, and so we look at what has the highest impact, and we insource that first, and then we slowly move down the value chain.”

This shows how the approach is pragmatic and not static. The company is moving to bring more electronics under its control, either by manufacturing components itself or through close collaboration with Indian contract manufacturers. The textile-heavy factory floor is a snapshot of its current priorities and not its final form.

Carbon Fiber Stretched

“We're nowhere close to the first companies in composites, right? Honestly, everyone in the drone sector uses carbon fiber, but what we've done differently is, I think, we've realized that there is a lot that can still be improved,” explained Naman. “You can go back to how we, as humanity, started using metals. We discovered how to smelt steel about 4,000 years ago, but you only started seeing metals at scale and advanced manufacturing processes about 200 years ago during the Industrial Revolution. We're seeing a similar story with carbon, where carbon exists, and people use it, but there are no processes that are really built around carbon.”

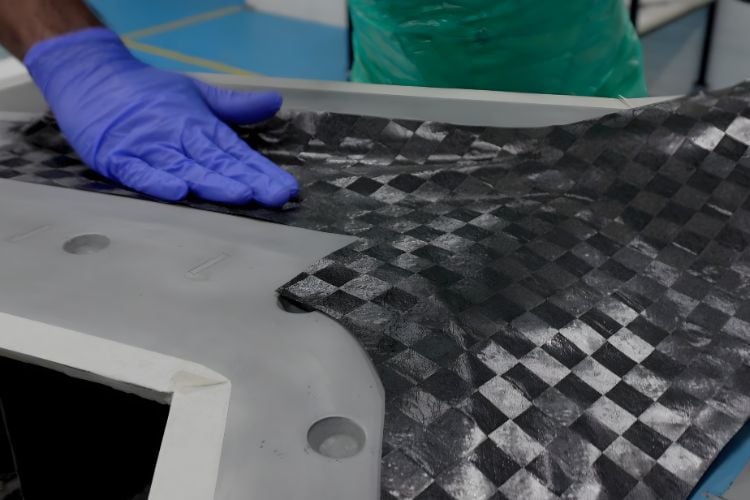

In the preparation area, we saw different types of fabric, fabric being cut, a release agent being applied to the mould to make it easy to separate the fabric from it later, and carbon fiber fabric in pre-preg form (carbon fiber already infused with resin) stored in a refrigerator so it does not cure prematurely. And in the layup area, we witnessed two carbon layers placed on a mould, sandwiching a layer of foam. Naman pointed out that most structures made out of carbon fiber today are just multiple layers of carbon fiber, which is not as efficient as this by far. In the vacuum bagging section of the room, a release film was being applied to prevent the fabric from sticking to the vacuum bagging film. Naman noted that it also doubles in purpose by absorbing a bit of excess resin as well. A breather cloth then goes over that to absorb excess resin, while benefiting from the release film that helps it not stick to the carbon material. A vacuum bagging film goes over the whole setup, it’s sealed tight, and then the excess air is sucked out through vacuum lines. Once vacuum bagged, the consolidation is sent to an oven to cure, which is followed by trimming.

The reason why trimming comes in this late is that carbon fiber, for all its strength, is still a cloth, and cloth tends to fray at its ends. Parts are intentionally made oversized, as trimming uncured carbon can get messy. Only after curing, when the resin has hardened the fabric into a solid composite, can edges be cleanly trimmed without issues. It's a reminder that even in advanced aerospace manufacturing, you're still working with materials that have their own stubborn personalities. Fortunately, carbon fiber's personality responds well to therapy, which in this case is resin and heat.

While processes can vary a bit, here’s a general flow of things.

- Layup

- Vacuum bagging

- Oven/cure

- Demould

- Trim

A drone is made up of roughly 18 different carbon fiber parts, including mounts, wings, and winglets. While carbon fiber dominates the build, a bit of Kevlar is used here and there. For example, the nose cone uses Kevlar, as carbon fiber would block radio signals like GPS. Also, Kevlar sandwich panels are used for internal midsection parts as they are easier to laser-cut.

I know this section is a bit of a stretch, a lot to take in. Some might call it a formatting mess… but I’m marketing it as a small nod to the tensile strength of carbon fiber.

Sticking to Glue

The assembly of the carbon fiber parts is a process that’s ruled by glue. One could say it’d be nuts to use bolts, as carbon fiber derives its exceptional strength from continuous strands running through the material. “If I drill a hole to put a screw in, that removes a lot of the strength, so we prefer to bond assemblies together. That's what gets you stronger parts," said Naman, hammering in the reasoning. However, he noted that the caveat is its toll on manufacturing, as strong glues typically take 24 hours to cure. To counter this, the company had to nail down a workflow that’s carefully orchestrated so drones are always at different stages of the production cycle, ensuring there’s always something curing. The target is to steadily output one to two drones per day.

Electronics: The Supporting Cast

Electronics has a dedicated room in the facility. It is compact by design as it does not demand the same sprawling space that their carbon fiber work does. The smallest room harbours the heaviest items that go on the drone; the Li-ion battery pack tops the list, with motors coming in second, “then you sort of move into relatively smaller components. A lot of the internal electronics adds up to a significant amount of weight. In fact, funnily enough, if you're just looking at stuff like, you know, your flight computer, ESCs, wires, etc., all of that total weight is about the same as the total weight of this entire frame,” elaborated Naman, gesturing at a drone suspended on a test stand. “We've created a lot of efficiency in this frame, but we've not yet done that with our electronics because, you know, if you're just looking at a default version, something of this size would probably weigh at least five to six kilos. So, we've had a massive weight reduction there, and now we're starting to look into, hey, how can we make our electronics lighter? How can we create our own wire harnesses? How can we move towards flex PCBs? How can we consolidate things? Because we know now that becomes a lower-hanging fruit. We've already created so much efficiency with the structure.”

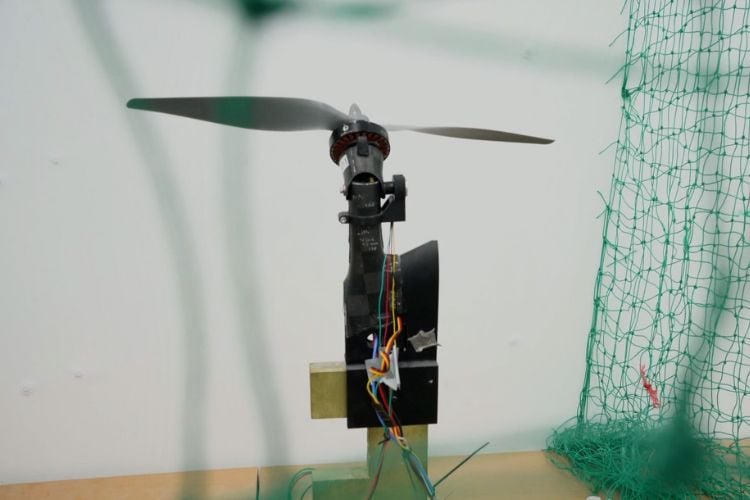

In our conversation with Mayank Joneja, the company’s Embedded and Autonomous Systems Lead, he attributed the simple electronics stack to the drones featuring just two motors, minus the bunch of servos enabling stuff like thrust vectoring. The entire system, powered by a 6s lithium-ion battery pack, includes servos for elevons (functionally a combination of elevators and ailerons) and a flap mechanism that opens to a space where the payload is kept, an antenna for remote control (letting RC pilots step in in case of emergencies) and two for telemetry, and a GPS module each for fixed-wing flight and vertical flight. The electronics bay houses the electronic speed controller (ESC), telemetry module, flight controller, radio receiver, and voltage regulators. While Airbound is not investing energy in reinventing the wheel with electronics right now, it recognizes the critical importance of these systems because, unlike mechanical issues that announce themselves with visible cracks, electrical problems can be invisible killers.

The Efficiency Dividend, Lithium-Ion

Let's address the elephant in the room, or more accurately, the elephant in the drone. Airbound’s choice of using lithium-ion (Li-ion) instead of lithium-polymer (LiPo) can be summed up in two words: operational longevity. The simple trade-off is that, in general, LiPo sacrifices longevity for performance, while Li-ion goes the other way a bit. From the standpoint of ‘economic’ drone deliveries, there’s a clear right choice, and Airbound can afford to make it, having racked up enough efficiency points in other areas.

Explaining the battery choice, Naman explained, “The main reason why drones use lithium polymer cells is because they have a higher power density. Drones consume a crazy amount of amps, right? And that takes a lot out of the battery; you're drawing an insane number of C's, which lithium ions are just not capable of outputting. What we realized is that if you want to move towards a good delivery system, you have to use lithium ions; you can't be working with lithium polymers… So this is where having a lightweight aircraft, having a high lift-to-drag ratio, high flight efficiency comes together to then let us use lithium ion cells.”

FWIW: When referring to Li-ion above, we mean conventional lithium-ion cells with liquid electrolyte, as distinct from lithium-polymer (LiPo) cells, which are technically a subtype of lithium-ion chemistry.

The Firmware-Rudra Duo

Airbound's flight control system splits responsibilities between two layers: firmware running on the drone itself, and a ground control software managing operations from below. The flight controller/firmware takes suggestions, not instructions, from Airbound’s proprietary ground station software, Rudra. And what this means is, a pilot can encode waypoints plotting the route for the drone, but how it covers it is up to the drone. With firmware running control algorithms at 200 Hz, the drone flies autonomously with the help of GPS and onboard sensors such as the accelerometer, compass, and gyroscope. However, if things go wrong, Rudra features interventions that operators can trigger through the press of a button.

The interventions that Mayank introduced us to were:

- Return to Launch (RTL) - calls the drone back to its point of origin

- Para-deploy - a parachute is deployed, allowing the aircraft to float down slowly

- Force Disarm - disarms the drone for scenarios when it's close to the ground

Most off-the-shelf ground control software isn’t built for the kind of stuff Airbound is trying to do. As a result, it’s building Rudra from scratch, using feedback from the pilots actually flying the drones. Rudra streams telemetry from the aircraft that relays its attitude (roll, pitch, yaw), speed, and waypoint progress, allowing operators to monitor multiple drones simultaneously from a single interface. “We want to build for scale, where we can monitor multiple fleets of drones, where we can enable kind of one pilot or operator to monitor multiple crafts at once, and also be agnostic to the actual uplink to the craft, whether it is 4G telemetry, or the current RF-based systems, or any other future systems. We want that flexibility in hand, and we also want to build it in an aesthetic way, or with the user kind of experience that reduces cognitive load,” shared Mayank, clarifying the need for in-house software.

Earning Their Wings

The company has something they call a static process, where they load firmware onto the drone and perform checks like validating the PWM values of servos that control the flaps that open and close the payload housing. It’s a final quality control layer intended to catch issues that could cause failures mid-flight and ensure that both hardware and software components work correctly before the drone ever takes flight.

We also saw a rig that’s in development, basically a massive test stand, which Naman described as a tool they use to replay logs and debug issues with the drone. In a soundproofed room, there were netted sections with jigs that allowed testing of different parts of the drone in isolation.

While software simulation kicks off flight testing, real-world tests are what actually reveal how the drone behaves. Airbound does at least ten different flights with a drone to validate flight behaviour before it goes into operations. Currently, the company is hitting hundreds of flights every day. When asked about the amount of flight data that they’ve gathered, Naman let out a laugh and said, “Too much.” Dealing with enormous loads of data has pushed the company to build custom databases and hire dedicated data analytics folk just to manage and filter through it all.

Naman explained why the data volume matters: “At the end of the day, if you want to put this out into the real world, it needs to be an incredibly reliable system. You need to have an insane volume of data to show that this is safe, and this can be put out there with a lot of humans nearby… It's very similar to… autopilot initiatives for cars, where they really look at how many millions of miles they've driven to prove that the data is safe. We need to do the same thing with however many kilometers we've flown, how many flight hours we've accrued, how many flights we've done.”

Fail Less, Fly Further

Look closely enough, and 10 paise per kilometer says more about how the company thinks than how it markets. The packed roadmap ahead includes evolving Rudra into a system that can handle far more complex flight-planning demands, especially as they move toward UTM-style capabilities. And that evolution is an absolute necessity, as the biggest needle mover when it comes to cost-cutting is scale.

While recognizing that anything in the air falls under strict regulatory oversight, Naman finds India’s policies progressive, allowing the company to conduct test flights without regulations being a bottleneck. At the time of writing this piece, Airbound has completed roughly 2700 flights from research to operations. Failures that once appeared every 20–30 flights are now seen only about once per 1,000 flights. This is a testament to how dozens of small refinements accumulate, each improvement a step closer to optimal. Fewer failures translate to higher regulatory clout, meaning that it’s not just the drones that are up in the sky, but also the company’s trustworthiness when things go well. To maintain that trust, Airbound takes aggressive measures to self-regulate and ensure its aircraft are truly fit for the real world.

Recalling Naman’s words: “No hobbyist cares about getting 10,000 miles of life out of their servos, even though it is possible. So why would any hobby manufacturer bother with that?” At low volumes, hobby-grade parts were simply what was available. But as production scales, the mismatch becomes clear: hobby supply chains aren't built for the reliability or volumes that Airbound needs. The path forward means bringing more of the supply chain in-house. Building an ecosystem of bespoke items is exactly what you’d expect from a company rewriting aerospace from its first principles.