Farming in India has been one of the most stressful occupations. Farmers have to face challenges like water scarcity, patchy power supply, and labor issues that consistently lead to poor yield. One of the biggest farming challenges in India is irrigation, which adds to the hardships of the farmers.

Understanding these problems and in the quest to help farmers with a technically advanced solution, Mr. Vijayeendra along with his co-founder started the company named Avanijal Agri Automation. The company manufactures agricultural-based systems and controllers to automate the entire agricultural process so that the farmers can save water, electricity and also avoid labor problems.

To discuss about the company, the agricultural automation process, and much more, we had word with Mr. Vijayeendra, who is the Co-founder and director of the company.

Q. Tell us about Avanijal and its plan for Digitizing Agriculture using Smart Irrigation Technology.

Our company is involved in the pre-harvesting activities on the farm which are primarily now the growing part of the crop. The farmer is involved in cultivating the crop, and then till the harvest, he has to take care of certain things which are irrigation and nutrient management. There are other activities too which we are not involved in terms of the de-weeding and other things like pest management. Our involvement is in helping the farmer in managing their irrigation and nutrient delivery using automated systems with the help of different technologies, which we deploy as part of the product.

Q. Starting from 2013, Avanijal has spent a lot of time understanding the market and perfecting their solution before commercializing their first product “Nikash”. What were some of the key findings you made during this time?

We started in 2013 and my other co-founder is from an agricultural family. He had a certain viewpoint about how things are done and how agriculture is practiced in India. We started from basics and we knew that we had to help the farmers in their irrigation management and we knew that the world is facing water problems, and India is no exception. We had other problems too in our minds that we wanted to focus on. We wanted to help the farmers with the technology intervention. Another factor that was in our mind was that agriculture is one of the areas which had the least amount of technology intervention more so, in India. I would say probably the same is true around the world in different places, but other countries are far ahead in this aspect.

We went around and looked at what are the problems that the farmers are facing and we saw that they have less water to irrigate which is one of the most basic problems. Secondly, to pump the water they need power (electricity), and there is a shortage of power in India. We might say that there are villages that are electrified, but that is true only to the extent of domestic electricity, but irrigation power is still facing a shortage. The irrigation power they get is only for about 6-8 hours. In summers, it is even lesser.

The third problem is that India, despite being a very populous country, and 60% of the people living in the rural areas of our country, it is hard to get good farm labor to manage farm activities, like irrigation, de-weeding, fertilizer delivery, etc. It is because the rural population is migrating towards urban areas in search of more stable income. Rural agricultural income is more seasonal, only when agriculture activity is going on, the labor gets money otherwise they have to engage themselves in some other activities.

The fourth problem is the lack of adoption of good agriculture practices. If you see the practices of agriculturists, most of them are still stuck in the practices that were being practiced decades ago, or what their father or grandfather was doing. Only a few people have adopted better practices by learning from the scientific community or looking at others and through their thought process evolution. At the same time, the scientific community's involvement in agriculture at a practice level is also low in terms of better interaction and better transfer of technology.

We also kept talking to different people to know more about practical problems other than these things. Taking these problems into consideration, we tried developing the product. We also researched the products that are already available in the market, and we came to know that most of the products are imported and not manufactured in India. Besides, we got to know that there are a couple of other companies, which are at our stage of starting the company in India and to develop these things, but they were in a very early stage. So, there were no set benchmark products for us to look at. We learned about the imported products, the features they provide, and if they are suitable for Indian farmers, their price points, etc. This all went into design upon production, and it took about three and a half years for us to develop this product.

Q. Can you elaborate more on Nikash and its variants? What are the bare minimum devices /components that go into farmland automation?

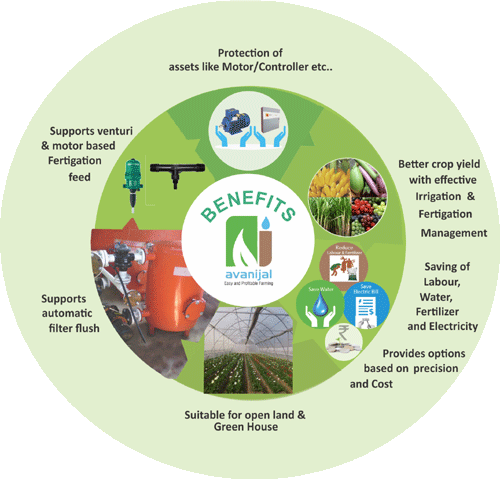

Initially, we planned to have a few variants of the product targeting different segments of the farming community, but later we realized that may not be the right model because a lot of people were asking for added features. So, we decided to make the basic product available with 20 other features (both hardware and the software functional features), which they can choose from at a different price and all adding to their basic product. So, that is the current model in terms of the offering.

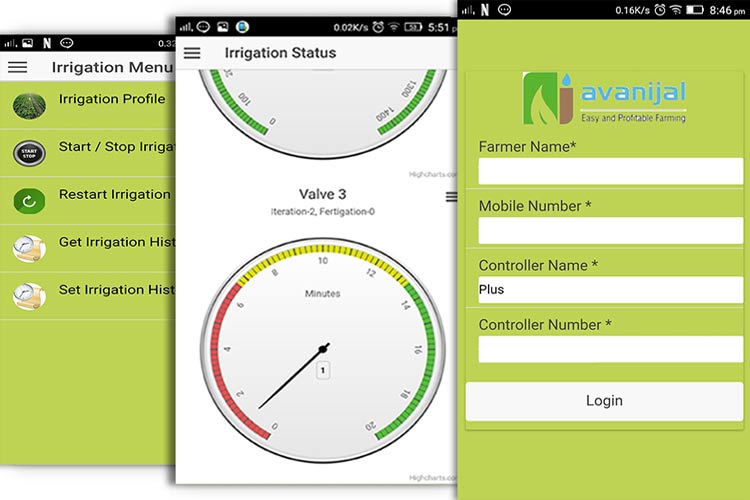

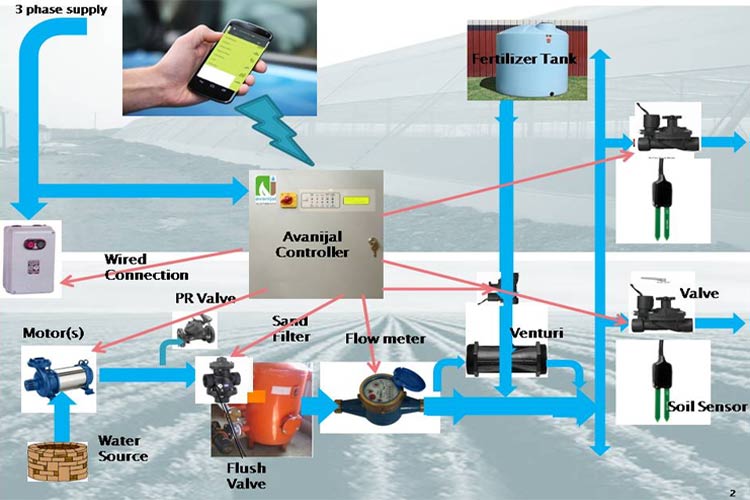

What helps the farmer at the most basic level is delivering the required amount of water to each part of the farm. Their farm maybe five acres or 10 acres, and they may be growing more than one crop on their farm. Each crop requires a different amount of water and different amount of nutrients and different types of nutrients. Once the system is deployed, they can program with the help of an app that we provide on their smartphone. They can program what they want to deliver, like how much water they want to deliver or how many nutrients they want to deliver at what intervals and for how long in a day or for how long at different intervals and things like that. Once that is done, whenever there is power available, the controller will monitor the power and voltages. So, that it does not go out of range for the pump to function correctly. That way, the pump is protected in the case of overvoltage or under voltage, and then it delivers the amount of water.

If you ask a scientist or an agronomist, they will say, deliver 10,000 liters or 12,000 liters of water per acre, but measuring water flow and then taking that feedback and then controlling is the next step that is a more precise way of doing it because it adds to the cost of flow meter and other things. Most people are used to delivering water by the time. There can be a lot of variation in terms of 30%- 40% in terms of based on the voltage variation, based on level of water in a bore well but people are okay with that and they can live with that kind of variation because they want to save cost.

Whenever there is power, it will deliver for one hour, two hours in two different zones. And at the end of the day, for irrigation, if the power is still there, it will probably wait for the appropriate time. Once irrigation cycling is done for all the areas, you wait for another 12 hours or 20 hours and then initiate the program. So, it will wait for that period, and then start the next day or start after four hours or whatever. This is the most basic functionality.

Besides voltage variation is the quantity of power available for farming and irrigation is one problem and the other is the quality of power or the voltage being in the range. Secondly, it is available continuously for six hours that is what the electricity supply companies say. And it's not true, every half an hour or one hour, 10 minutes, there is power interruption; it keeps going and coming back. It creates a lot of problems or even for the farm labor to go and turn it on, turn it off and set the valve whichever valve has to be turned on at any given point in time. When the power is available at the night, nobody wants to go to the farm and then manage the irrigation, including the owner of the farm; he will not want to go because it is risky as there could be any creature. The product our company manufactures addresses these kinds of difficulties.

Nikash claims to improve crop yield and reduce water consumption, how practical is it for small or mid-sized farmland? Can you explain with any case study?

For individual farmers, anybody who has land of five acres or above can use our system. It is cost-effective as they can get back their returns and all the investment in terms of labor cost saving as well as yield improvement, which is purely economic for a farmer. They can get back their money in about one to two years, provided they're growing medium to high-value products. These are not very suitable for Paddy and wheat because they are the most staple crops. It could be used for any horticulture crop, be it coconut, banana, papaya, any fruit, flowers, pomegranate, grapes, etc.

For small farmers, there is another way to use it. If somebody has one acre or two acres of land, he can use the control system by community farming method. Let's say four or five farmers are coming together to use this system. One control system can be deployed for four or five farmers; they can share the cost of the controller and still get what they want to be done in terms of their irrigation and nutrient management.

Secondly, let's say if you have only one source of water to be delivered to multiple farmers. Our control system can act like a multi-user system for up to four users and then from one of their water sources, it can deliver water. This way, each farmer can control their part of their water source and delivery of water. This way, the cost of the controller can be shared. This will enable a small farmer to be able to use it without bothering about the expense. In some of our customer cases, farmers do not buy the product directly, but it is enabled by an NGO which is helping the farmers in this case.

Q. What are the different kinds of sensory data that are collected from the farmland? What analytics is done on this data and how does it help in increasing the irrigation efficiency.

Right now, we are collecting data, but we are yet to do the analysis, which is in our plan for the immediate future. The kind of data we collect is the amount of irrigation that will take place (time and volume). If one adopts a flow meter, they can precisely deliver 8000 liters, 9000 liters, or 10,000 liters per zone, whatever is there on the plan. That is the one thing they can program. So, the amount of water delivered, the amount of fertilizer delivered either in time or volume that is what is gathered. That is probably the most important thing in terms of Agronomical analysis, which is what we are planning to do.

Let's say you have this data, along with other data, in terms of what were the ground conditions and the atmospheric condition at that time. Once you have that, an agronomist can look at that whole data for the whole cycle of the crop and then suggest better practices for the next cycle that is at a very macro level. This is what we're planning to do going forward.

The other data that is collected is how long was the power was available, when did the power come. This kind of data will be available for other stakeholders in this whole process in terms of optimizing the power supply that may be useful.

Initially, we wanted to see whether we can deploy an ‘on-the-ground sensor’ for soil moisture sensing, soil temperature sensing, and gathering weather data with temperature and humidity, etc. For every zone, the unit deploys these sensors, at least for the soil and one sensor for the atmosphere as a whole. Practically, there is no company I would say which has developed goods sensors, which can be deployed very easily. So, we had to import and do the integration with our solution, but what we realized is that they are so expensive that it becomes impractical for a farmer to deploy for every zone. So, we looked at other alternative solutions that could give similar data and what can help the user, though it may not be as accurate as real-time, but it comes at a very low cost.

What we are trying to offer now is satellite image-based sensing. Deep Learning Artificial Intelligence is applied to the image, which is acquired from multiple satellites both visible and radar data. This image process data is also crunched with the weather data for that particular area in terms of what is the air temperature, humidity, etc. And then a recommendation for that day is made available. Our controller is integrated with that kind of system which is offered by one of our partner companies. Our controller tells the amount of water irrigated on a particular day. The system will collect all the data, and it will be easy to compute the entire data in a few seconds. The only on-the-ground sensor we may have to deploy would be the rain sensor. Rain is a very discreet event and India has very small climatic zones. If it rains a lot, we may have to stop irrigation. Other than that, all other data comes from multiple satellites.

Q. Replacing these sensor nodes with satellite images is part of the plan. How far have you tested this and how feasible? Could it be a viable replacement for the ground sensors?

Yes, it’s a viable replacement; only thing is that after you deploy the on-the-ground sensors correctly, you have to calibrate it correctly, which may take a couple of days. But in the case of satellite image processing-based sensing, it takes a couple of weeks for the values to be stabilized. But, if there are a few more sensors deployed and other areas are covered, probably the learning time can be reduced, but it will take a couple of weeks in a new zone or area, where we deploy for it to learn and it is very economical.

It can cost a couple of 1000 Rupees per acre per year for a farmer to use this kind of system. We are still in the early stage; the accuracy is supposed to be about 80% to 85% compared to the on-the-ground sensor, so that way, it is pretty accurate. You don't need 100% accuracy for agriculture sensing. So that way, it is a pretty practical solution. But it will take time. People still may not believe in on-the-ground sensors. When you tell them that I don't deploy anything on the farm, but I can still tell you what you need? They don’t believe. Farmers will take time to believe in the technology, however, we have started doing it for few customers.

Q. Providing wireless connectivity to the different nodes across the farmland should have been a challenging task. How did Avanijal deal with it? Which wireless protocols are you using, and why?

Currently, our control system which is deployed along with the actuators requires some rain-proof shelter as it's not IP Ingress protected box. So, we didn't feel that is very necessary because anybody who has this; they have some kind of shelter, even if they don't have a room. We have been able to deploy it in standout boxes like syntax boxes or some kind of metallic box, wooden or cement boxes, which is good enough. It has to be a rainproof shelter, and it works well at higher temperatures, obviously at 40-45 degrees kind of geographies in India. But the biggest challenge we faced anywhere is the quality of the power.

The variation of input power is so high that we had to redesign our power supply circuit many times to be able to meet the widest range and then protect our system from all the issues created by this kind of incorrect deployment or incorrect supply issues and there are even many places where farmers use bad methods to tap power. Power tapping creates a lot of spikes and surges on the system that burnt a couple of controllers before we realized what was happening. Now, we have designed it in a way that stimulates the whole system. Obviously, along with our control systems, we have installed some accessories to be able to manage this properly. We have realized and understood that we should not design everything ourselves, we should use what is available off-the-shelf and what is economical. That way, the full solution is very affordable for the farmers.

Secondly, lightning can cause damages because the wires are spread out through the farm, any kind of lightning can damage. You cannot protect against lightning, but you can only take some precautions. So, the way we design our box and cabling and all that it is very easily removable, the cables are easily removable. You can also turn off the power to protect the controller during the rainy season. Another way of handling the damages is insurance that can help you save cost to repair, and get a warranty, etc.

Also, awareness among the farming community is the biggest challenge in terms of penetrating our market reach. Secondly, farmers have been used to not paying the full amount because they get subsidies for a lot of different things they buy. The automation systems are not subsidized by most governments, though, Karnataka government declared they will have something but I think it did not get rolled out probably in the most efficient way; maybe it's still not there actually.

We work with solar power also, and it has its challenges in terms of variation due to the radiation. We have done some improvements, and we have tested our product in the early stage, which can be tested normally, in one day, we had to take about four or five days because power is available only for three hours or four hours on the farm, so we had to wait till next day before continue with the testing.

Q. You have already tested the satellite imaging technique in few places and it is a viable replacement for the probe sensor? Can we expect that your company will completely pivot into this satellite imaging system instead of a probe system? Do you think you will make a complete shift over?

As of now, we are not offering on-the-ground sensing as part of the Avanijal solution. If somebody wants it, we have other companies who may supply that, we may integrate with that, but right now we are not even talking about it because once you talk about it, then they will ask for the price. And once you tell the price, and then say I don't want it. So, there is no point in wasting a lot of time telling that sensing is available but at this price. There is no point in trying to drag them to deploy a very expensive solution.

Even in western countries, people can't afford these solutions, even if they have large lands, it's very difficult. So, on-the-ground sensing is not a very practical solution. There may be other service providers like this who may want to collaborate with more than one such satellite image processing recommendation service provider, and you may integrate with them to be able to offer customers different choices. But I think that is a way to go. The reason is that it starts at a lower cost, though it is not very accurate and it has its own learning time. As time goes by, because it is a learning system, it will get better, and it cannot get worse.

Another problem with on-the-ground sensing is as the roots go deeper and deeper; you have to keep shifting the height of the sensor. Secondly, whenever you are changing the crop, you have to change the depth and take it out and then redeploy all of these practical issues. They're too cumbersome for anybody to do that. And, it'll have its maintenance, annual maintenance fees, etc. which I think will be very dissuading for any user to deploy.

Q. How many installations have Avanijal completed so far? How do you see the response from farmers so far?

We started selling 3 years back and we have about 40-45 installations so far in a few states in Karnataka, Maharashtra, UP, etc. Most of the farmers are either having 5 - 10 acres, and one farmer has about 100 acres of land in Maharashtra. The beauty of that is if the irrigation system is well designed, our solution can manage even 50 to 200 acres. We don’t say that our controller does everything but the irrigation system which is designed underneath this also has to be properly designed, only then you can get the benefit of this since it is a layer of irrigation basic irrigation system.

Q. How do you see the market for Smart Irrigation in India? How are you planning to expand and reach potential customers?

In India, I would say, it is still nascent because the awareness itself is lacking in most people. Only a few percent of the farmers, maybe less than 5% of the farmers want to try on their own. First of all, it requires micro-irrigation to be set up. Practically, micro-irrigation penetration in India is quite low.

If you assume that 25% of the farmers have deployed, out of that 85% of them will be small and marginal farmers. On their own, they will not be able to deploy this kind of thing, somebody has to help them or they have to come together on a cooperative basis. So, what it leaves is about 10 - 15%, and then again in that small percentage of farmers are aware, and then they want to try it out.

So that way, at this stage, it is very nascent but still catching up. If you ask me, I would say five years ago, people didn't even know what sensors and sensing technique is. But today, we are getting so many calls on asking for an automation system and the immediate question they ask is, do you have sensors, do you provide them, and things like that. And people think that okay because, in the early days, imported systems were very expensive, and they may be our system is also very expensive. Our system probably costs about 20 - 25% of the imported systems. That awareness about the economics of that also has to come into the picture and we being a small company, we cannot disseminate this information largely in a local area, but we are using digital means to do that. We do not have our sales and support force in our area of geography, but we work with partners and irrigation companies, and other irrigation service providers to spread this message as well as sell and deploy.

This will take a lot of time, but I think outside India, it is a very mature market and there is a lot of potentials. But in India, I think it's still catching up. It may take a few years for it to take off in a big way. But I think any government intervention like a subsidy for these kinds of things might have a certain positive effect also, provided it is done well.

To sum up, Mr. Vijayeendra told us that by using the solution, the farmers get benefitted directly as it helps them save money and earn more money that happens in two ways. One is saving the labor, there are a lot of people who are not able to get any labor and they are deploying our automated system. Secondly, with better handling of water and fertilizer, they certainly get better crop yield, which helps them get more money from the same amount of resources they are deploying. These are the direct benefits but there are other ways in which the farmer get benefitted which he may not see today, there is water being saved, better utilization of water takes place, increase in water use efficiency takes place, which will help the society as a whole in reducing the water usage in farming which is up to 75 - 80% i.e. direct agriculture and if you take other food processing areas, it will probably hit close to 90%. So, what is left for the remaining industrial and domestic purposes is 10% to 15%.

If you reduce water usage in agriculture, probably which is possible by deploying micro-irrigation as well as the use of such better methods of automating, sensing, and delivery. You will save water and use less fertilizer. So, that saves costs as well as use less fertilizer to grow the same amount of crop would help reduce the soil contamination, which has been a big issue in some places in India, due to which people have been getting contaminated water and that has led to diseases. So, there are other societal benefits too. Once this is done well, energy consumption also goes down. Also, a lot of people still think that irrigating more water will lead to better crop yield, which is not true. Researchers have shown that if you over irrigate, the yield will start reducing. So, if you irrigate the right amount of water, you will save water and energy as well. The energy consumption by the agriculture sector is close to 20% which certainly can be reduced with all such measures being taken. These kinds of interventions will help the individual farmers as well as the society in utilizing the resources better.