The international scarcity of semiconductors that has affected sales and manufacturing in numerous countries shows no sign of recovery until 2024. In fact, it has left several bigwigs and international lords at multinational companies extremely worried about this incident. The supply now is very limited when compared to the current global demand and the supply hindrance would likely persist throughout the end of 2023, claims experts. Although a lot of international companies are involved in scuffles to escalate production, the crack is more likely to widen before there is any mending. Of late, multinational semiconductor firm Intel’s CEO, Pat Gelsinger stated that the worst situation is yet to arrive and it will be at least a year or two before supplies return to normal. In this aspect, we spoke to Mario Morales, Group Vice President, Enabling Technologies and Semiconductors, IDC about when supplies of semiconductors would become regular, the various challenges affecting the industry, and when the situation can be stabilized and how.

Q. In light of the current semiconductor crises, what are the various obstacles affecting the sector now, and what is the current situation?

The shortage is shifting from the front-end manufacturing area to the back-end and material side of the market. Utilization rates are at 100% for the largest dedicated foundries, however, back-end Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT) companies are struggling with rolling power outages, workforce, and underinvestment. I expect this is where the challenge for the industry is next after the initial concerns about fabs not having enough capacity to meet demand.

Q. You as a global semiconductor researcher when do you think this one-year-long stressed challenge will be over? Also, do you think excessive investment in this sector will lead to over-capacity?

Foundries are close to catching up to demand (Q3 '21), however, OSAT companies, material suppliers, and product sectors like quartz, substrates, power supplies, power management, and passives are still seeing lead times extend excessively. We expect to see a balance by the middle of next year with the potential of overcapacity in 2023 if all the capacity planned comes online and IDC’s demand scenario changes. We also expect the semiconductor market to grow by 17.3% in 2021 versus 10.8% in 2020. The augmentation is spearheaded by mobile phones, notebooks, servers, automotive, smart home, gaming, wearables, and Wi-Fi access points, with escalated cost in memory. As there are chances of capacity additions to accelerate, IC slumps are also speculated to continue to smoothen through Q4 2021. At this moment companies such as TSMC, Intel, and several others are expanding their capacity with increased investment because it is now needed without any delay and even if there is any glut it can be used further in difficult times.

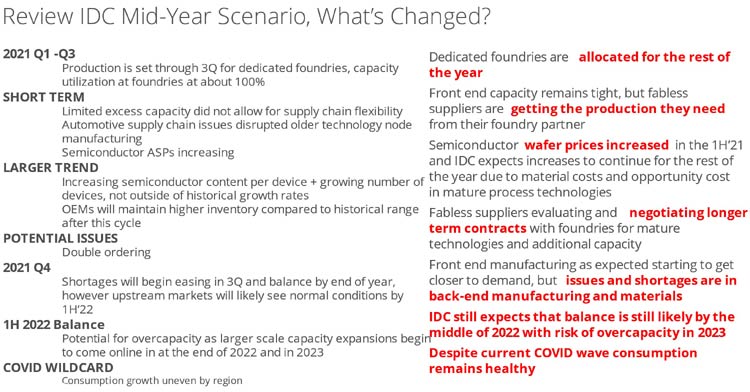

Supply constraints begin to ease by the end of Q3 if you are a large vendor in the ICT area. Vertical markets like industrial and automotive will see a balance in the 1H '22 given that their supply chains are less efficient and don’t have the volume and scale of PCs, mobile phones, and data centers. Tier 1 OEMs are getting priority volumes but likely ordering more than they need, while lower tier and smaller enterprise vendors are seeing extended lead times and price increases which are also forcing them to double order. The slide below shares our supply scenario.

![]()

Q. Currently, which are the countries leading the Chipset production/manufacturing race? Where do you think India stands in this global competition and what it should do to become globally competitive?

A large part of the front-end and back-end manufacturing is done in Taiwan, China, S. Korea, and Southeast Asia. India’s semiconductor manufacturing is almost nonexistent. India has a high concentration of design services and software development which is the focus for the region and a critical part of the overall value chain. Infrastructure and natural resources like logistics, transport, water, and energy is critical part of the manufacturing supply chain. Looking ahead, India needs to dramatically improve its infrastructure in order to attract manufacturing investment in the future. Local brands are looking to source more locally (given the tension with China), however, the scale and infrastructure that China has is very difficult to replace. That said, I expect to continue to see more semiconductor companies and Electronic design automation (EDA) companies invest more in India like Qualcomm, Intel, Cadence, Synopsys, AMD, and others you will gradually see the need to invest more in the country by the government in order to sustain the requirements of these foreign and domestic entities who want to address the large potential market in India.

Q. The demand for electronic items and automobiles is escalating every month, but this chip crunch is cutting back production. For instance, Renault’s production will hit 5,00,000 cars in 2021, as per reports. So, how do you think the situation could be stabilized and when?

The automotive industry will be one of the industries that will take the longest to recover given that the industry moved to the end of the line in 2020 and has been gradually recovering. Suppliers are supplying chips now for automakers, but there is still a bottleneck as the parts move upstream and ultimately make it to the end system. I expect the auto industry will take until the 2H’22 to recover as it moves away from just in time processes and suppliers begin to establish long term agreements with tier one OEMs in the automotive industry so they don’t get burned by the pushouts and cancellations they experienced last year when the pandemic and shutdowns brought uncertainty to the supply chain.

Q. Can you please highlight some of the additional challenges the global foundry capacity is facing?

Overall, dedicated foundry capacity is fully committed for the rest of the year in the mature technology areas which include production of SSD controllers, display drivers, image sensors, analog, and power management PMICs. Taiwanese fabless companies and other suppliers serving the memory ecosystem are telling us that lead times are stretching to 18-20 weeks (normal is 4-6 weeks) which is forcing them to order capacity ahead of schedule to get access in 2022. The challenge and common denominator for Auto ICs, PMICs, image sensors, and controllers in shortage are that the majority of their needs are being met by the same process technology. Mature technologies (40nm and older) account for over 50% of the total industry capacity. UMC, GF, SMIC, and TSMC are only investing incrementally in these nodes at this point and will only invest if the company can establish longer-term commitments (multiyear) with key customers like Qualcomm, NXP, Broadcom, Novatel, Realtek, TI, Microchip, Holtek, and MediaTek. In the meantime, foundries will only incrementally increase wafer volumes for their existing and depreciated capacity. This reality is also being overshadowed by the Chinese ecosystem which has built plenty of mature technology capacity over the last 6 years but is being hindered by a lack of talent, inefficiency in operations of the plants, and a political and trade climate that is not allowing them to scale. The Taiwanese will not build a new plant to address mature technologies knowing the capacity that exists in China. The preferred strategy for Taiwanese Foundries will be to leverage depreciated capacity and establish long-term supply agreements with customers.

Q. Can you please highlight some latest research reports or some key findings by IDC on the development of global semiconductor firms to strengthen their foot again?

TSMC in their latest earnings report has said that they have caught up to orders from their customers this past quarter and the real bottleneck is moving the product upstream to the end markets. Wafer fab spending has been increasing strongly since 2019, and we expect it to remain strong from 2021 to 2023. TSMC, Samsung, and Intel who account for more than 50% of spending will each spend strongly which will bring on a large amount of capacity in the 2024 time period and beyond.

We believe that the price increases for Dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) are sustainable until the end of this third quarter. The DRAM memory market bottomed in Q1’21, after going through some inventory digestion since Q3’20. Specifically, Cloud Service Providers (CSPs) began ordering again after their pause last year. This has helped stabilize pricing and now allows for increases given the surge that was not expected by suppliers. The NAND market is more uncertain and I would be more cautious on NAND supply because I still believe that it exceeds demand and the constraint for NAND is primarily on controller technology. Pricing has started to see pressure in October and product availability increases in the channel.

One that is being overlooked is the fact that semiconductor content has grown dramatically over the last 5 years in areas like mobile phones, servers, PCs, and communications infrastructure which suppliers underestimated but should be factored in to explain the constraints we are seeing now. There is a growing bottleneck for advanced packaging, substrates, and materials for OSATs which we are looking into more closely which could extend our scenario by a quarter or two.